Important note: Multi-Document ACID Transactions are now available in Couchbase. See: ACID Transactions for NoSQL Applications for more information!

ACID properties are a topic that I get asked about a lot. Generally, people ask in the context of transactions: “Are there NoSQL transactions?”, “Can I use ACID transactions in Couchbase?”, and so on. But today’s distributed applications do not always expect or need all of the ACID properties from their database. I’ll dig deeper into how NoSQL and ACID properties come together in Couchbase.

Before we do that, let’s define what we’re talking about. ACID stands for: Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, Durability. It was coined in the 1980s, but has existed since the 1970s in traditional, non-distributed, relational databases. It describes a class of database that is capable of providing operations with ACID guarantees.

Couchbase and Transactions

Scaling, performance, and flexibility have been the core focus of the Couchbase data platform, and distributed, multi-document transactions are often at odds with these characteristics.

Part 1 of this 2-part blog post is going to cover the building blocks of ACID that are available in Couchbase. You can use these “primitives” without sacrificing the overall scaling, performance, and flexibility of Couchbase. Depending on your use case, these primitives might be adequate on their own, or in concert with each other.

Currently, Couchbase supports many ACID properties on single documents, but does not provide multi-document transaction support. In part 2 of this series, I will show an approach that uses these building blocks to make something like a multi-document transaction with Couchbase. But first, it’s important to have a complete understanding of the building blocks.

What are the ACID properties?

Applications have evolved from monolithic all the way to distributed micro-service based applications. Microservices still expect certain aspects of transactionality such as an atomic commit or rollback, but not necessarily full ACID behavior. Full ACID behavior may still be important, but in modern web and mobile software, it is often lower priority to performance and scalability. However, it is not an “either/or” situation. Couchbase provides some tools and capabilities to help you balance ACID properties and performance.

A is for Atomicity

“Atomicity” means that a group of operations either all succeed or all fail. Couchbase provides atomicity for single documents. An operation to get or set a document either succeeds or fails. Compared to an RDBMS guarantee of multiple operations succeeding or failing together, this may not seem like much.

But consider that data modeling is very different between document databases and relational database technologies.

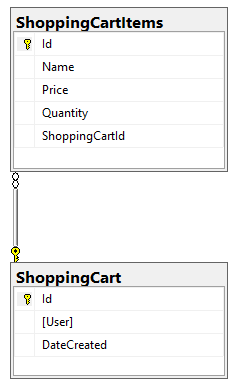

In a relational database, you typically normalize the data. For instance, to store a a shopping cart with 3 items, you would need:

- 1 row in a ShoppingCart table

- 3 rows in a ShoppingCartItems table

If you want to create a shopping cart with 3 items, this requires four INSERT statements. So, you might need your relational database to treat those 4 statements atomically.

Now consider a document database. You would create a single shopping cart JSON document, which would itself contain 3 items.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

key cart::001 { "user": "Matthew Groves", "dateCreated": "2018-03-22T13:57:31.2311892-04:00", "items": [ { "name": "widget", "price": 19.99, "quantity": 2}, { "name": "sprocket", "price": 17.89, "quantity": 1}, { "name": "doodad", "price": 20.99, "quantity": 5} ] } |

Getting or setting this document is a single atomic operation in Couchbase. A fully normalized model isn’t often needed. If I were to extend this model to include address, and my address changes a month after I ship an order, does the order to which the address was shipped actually change? Normalization partly aims to reduce data duplication. This is the correct and efficient thing to do in some situations, but not all.

If you can model your data like this, then you immediately reduce your need for a multi-operation transaction (if you’re concerned about ballooning document size, don’t worry, you can use a subdocument or N1QL operation to operate on a portion of the document).

C is for Consistency

“Consistency” means generally that an operation “won’t violate declared system integrity constraints”. Any constraints in the database about the data remain consistent before and after an ACID operation. For instance, if an atomic set of operations fails, then the data remains consistent with what it was before the operation (because it can be rolled back). There are other types of consistency constraints that a database can impose: in a relational database, for instance, you cannot insert 6 columns of data into a 5 column table.

Instead of a schema, Couchbase uses JSON. Every document implicitly contains its own schema. If you perform an insert operation with JSON, you must supply valid JSON (the Couchbase SDKs will typically handle this for you). Couchbase only enforces this at the document level. Couchbase cannot prevent you from using a different JSON schema from document to document. For instance, consider these two documents:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 |

key user::001 { "user": "Matthew Groves", "dateCreated": "2018-03-22T13:57:31.2311892-04:00" } key user::002 { "userName": "Matthew Groves", "the_date_created": "2018-03-22T13:57:31.2311892-04:00" } |

A Couchbase bucket allows both of those documents. Note that the field names are not consistent with each other. This means that there is more responsibility at the application level to ensure the documents have consistent naming (but typically, this will be derived from your data model, and thus is handled automatically).

Another constraint that Couchbase enforces is the key. Each document must have a unique key. If you try to insert another document with a key of “user::mgroves”, for instance, an error will occur. So if you need to enforce a unique constraint, using the document key is one way to achieve this. (It is also to your advantage to use a natural key when possible so that a Couchbase cluster can perform a direct lookup).

Query Consistency

Finally, I want to mention index consistency. With the N1QL query language, Couchbase is able to index fields or combinations of fields in JSON documents (just as relational databases can index columns or combinations of columns). However, Couchbase updates indexes asynchronously to provide better performance than other types of databases. When executing a N1QL query, the default behavior is “Not Bounded”. This means that the query engine will return results based on the current state of the system. So, hypothetically, if you create a new document and immediately run a query, that document might not be in the results.

Fortunately, there are two other options to tweak the consistency of queries: RequestPlus and AtPlus.

RequestPlus is at the opposite end of the consistency spectrum. It will wait for any documents currently known to the cluster to be part of index recalculations before processing the query. The trade-off here is latency, of course. A RequestPlus query will possibly take longer to execute.

AtPlus is in the middle. Instead of waiting for an entire index to complete, AtPlus will only wait for indexing of the documents known to a particular instance of your application. This provides lower latency with a narrow window of consistency, but it requires more work for the SDK. The query request also needs to be handled by the same instance.

Note: The “Consistency” in ACID is different than the “Consistency” in the CAP theorem. When thinking of Couchbase and CAP, remember this is a strongly consistent distributed database. This means that each document has a single correct document per cluster, and there cannot be a “conflicting” or “sibling” document with the same key elsewhere in the cluster. A strongly consistent database does not imply anything about transactions or ACID properties.

I is for Isolation

“Isolation” is the ability for an operation to occur only after another operation on the same data has been completed. In this way, each operation is independent of other operations. This is very important when a database is handling concurrent data access. It should appear that the database is handling only one operation at a time. In order to accomplish this, the data that’s being updated must be locked out of being modified (and/or viewed) until the operation is complete.

Couchbase provides read committed isolation by default at (again) the single document level.

To get stricter isolation, there are two types of locks that you can do in Couchbase: pessimistic locking and optimistic locking.

Optimistic locking

“Optimistic” locking hinges on a value in Couchbase called CAS (compare-and-swap). Every document has a CAS value, which is some opaque value. Every time that document changes, it gets a new CAS value. When you attempt to update a document, you pass a CAS value as part of the operation. If the CAS values match, Couchbase allows the operation. If not, the operation is not allowed, and Couchbase returns an error instead.

As an example, let’s suppose there are two processes: A and B. A and B both make a “get” request to Couchbase to fetch a document. Couchbase returns the document, along with a CAS value. Then, A and B both send a “set” request to Couchbase, passing along the CAS value they previously received. Processing will race, occurring on one of them first. Let’s say it’s A. When it’s B’s turn, the CAS value of the document has already changed, and so the operation fails.

Here’s an example in .NET. Let’s suppose we’re working on a mobile game, and we want to keep track of a player’s Sword Level. The higher the level, the more damage it does. In this example, A is trying to upgrade to level 2 and B is trying to upgrade to level 3.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 |

// create initial document bucket.Upsert("myweapon", new {offenseLevel = 1, name = "Excalibur"}); // document is retrieved by two different applications (A and B) var weaponAResult = bucket.Get<dynamic>("myweapon"); var weaponA = weaponAResult.Value; var weaponBResult = bucket.Get<dynamic>("myweapon"); var weaponB = weaponBResult.Value; // at this point, CAS values should be the same if (weaponAResult.Cas == weaponBResult.Cas) Console.WriteLine("CAS values are currently the same!"); // A makes a change Console.WriteLine("'A' is updating the document"); weaponA.offenseLevel = 2; IOperationResult aResult = bucket.Replace("myweapon", weaponA, weaponAResult.Cas); if (aResult.Success) Console.WriteLine($"Change by 'A' was successful. New CAS value: {aResult.Cas}"); // B tries to make a change too Console.WriteLine($"'B' is (attempting to) update the same document using old CAS value: {weaponBResult.Cas}"); weaponB.offenseLevel = 3; IOperationResult bResult = bucket.Replace("myweapon", weaponB, weaponBResult.Cas); if (!bResult.Success) Console.WriteLine($"Change by B failed: {bResult.Exception.Message}"); |

At the end of this process, B fails, and the player’s sword stays at level 2. If you want B to succeed, then one solution is to re-fetch the document, get the latest CAS value, and try again.

Of course, that solution could fail again. And again. But this is why it’s called “optimistic”. It assumes that the document is not going to be under heavy contention, and it will eventually succeed. There is no actual locking by the servers required: just a check of values.

Pessimistic locking

You can use pessimistic locking to actually set a lock. This can be useful if you want to lock a document graph to mutate multiple documents.

There is an atomic operation available in Couchbase called “GetAndLock”. This operation returns the document and a CAS value. At this point, the document is considered “locked”. No more locks can be made on it by other processes, and only the CAS value can unlock the document.

Here’s a C# example of a pessimistic lock in action:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 |

// create initial document bucket.Upsert("myshield", new { defenseLevel = 1, name = "Mirror Shield" }); // document is retrieved and locked by A var shieldAResult = bucket.GetAndLock<dynamic>("myshield",TimeSpan.FromMilliseconds(30000)); var shieldA = shieldAResult.Value; // B attempts to get and lock it as well var shieldBResult = bucket.GetAndLock<dynamic>("myshield", TimeSpan.FromMilliseconds(30000)); if (!shieldBResult.Success) { Console.WriteLine("B couldn't establish a lock, trying a plain Get"); shieldBResult = bucket.Get<dynamic>("myshield"); } // B tries to make a change, despite not having a lock Console.WriteLine("'B' is updating the document"); var shieldB = shieldBResult.Value; shieldB.defenseLevel = 3; IOperationResult bResult = bucket.Replace("myshield", shieldB); if (!bResult.Success) { Console.WriteLine($"B was unable to make a change: {bResult.Message}"); Console.WriteLine(); } // A can make the change, but MUST use the CAS value shieldA.defenseLevel = 2; IOperationResult aResult = bucket.Replace("myshield", shieldA); if (!aResult.Success) { Console.WriteLine($"A tried to make a change, but forgot to use a CAS value: {aResult.Message}"); Console.WriteLine(); Console.WriteLine("Trying again with CAS this time"); aResult = bucket.Replace("myshield", shieldA, shieldAResult.Cas); if(aResult.Success) Console.WriteLine("Success!"); } // now, the document is unlocked // so B can try again bResult = bucket.Replace("myshield", shieldB); if (bResult.Success) Console.WriteLine($"B was able to make a change."); |

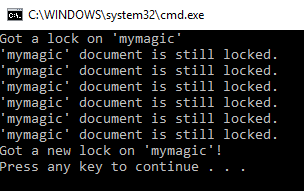

Further, when using GetAndLock, you must set a timeout period. After the timeout period, Couchbase releases the lock automatically. Here’s an example of the timeout in action.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 |

bucket.Upsert("mymagic", new { magicLevel = 1, name = "Fire Magic" }); // alternatively, if A never gets around to releasing the lock // then the lock will automatically be released after a certain time var magicAResult = bucket.GetAndLock<dynamic>("mymagic", TimeSpan.FromMilliseconds(5000)); if(magicAResult.Success) Console.WriteLine("Got a lock on 'mymagic'"); // try to get a new lock every second for (var i = 0; i < 10; i++) { var magicBResult = bucket.GetAndLock<dynamic>("mymagic", TimeSpan.FromMilliseconds(5000)); if (magicBResult.Success) { Console.WriteLine("Got a new lock on 'mymagic'!"); bucket.Unlock("mymagic", magicBResult.Cas); // unlock it right away break; } else { Console.WriteLine("'mymagic' document is still locked."); } Thread.Sleep(1000); } |

When running this example, the following output would occur:

Using these locks, you can obtain isolation of an individual document, to make sure that changes happen in the order that you expect.

D is for Durability

“Durability” traditionally means that when an operation completes successfully, that the disk stores the changes made by the operation. In a distributed database, durability can mean that the disk and/or the memory in other nodes store the changes. Replication to other nodes is the preferred mechanism for durability in Couchbase as the network is much faster than disk. Ultimately, to a developer, it means that even if a system failure occurs, the change still takes place.

Couchbase has a “memory-first” architecture. This means that the results of write operations are acknowledged when received to memory, and then put into a queue to be asynchronously written to disk or replicated to another node soon after. So, if an operation writes to memory, and the system shuts down immediately, then that operation is not durable. This is the default trade-off that Couchbase makes: speed over durability.

However, Couchbase allows you to override that default configuration and specify a stronger level of durability with Durability Requirements. This will swing the pendulum away from performance and towards the ACID properties. The benefit of this design is that the application developer knows and decides when it’s important to pay the extra cost.

The default behavior is that writing the document to memory is considered a success. Couchbase will still persist and replicate according to your Couchbase cluster configuration, but the method call will proceed after the operation is acknowledged.

|

1 2 3 4 |

// default memory-first var result1 = bucket.Upsert("memory-first", new {twitter = "@mgroves"}); if(result1.Success) Console.WriteLine("Success"); |

I can specify the number of nodes to replicate to that I consider to be a successfully durable operation by using ReplicateTo:

|

1 2 3 4 |

// replicate var result2 = bucket.Upsert("replicate-to-1", new { email = "matthew.groves@couchbase.com" }, ReplicateTo.One); if (!result2.Success) Console.WriteLine("This will also fail if I only have 1 node"); |

And I can also specify a combination of persistence to other nodes and replication to other nodes that I consider to be durable “enough” by using PersistTo as well:

|

1 2 3 4 |

// persist and replicate var result3 = bucket.Upsert("replicate-to-1-persist-to-1", new { site = "blog.couchbase.com" }, ReplicateTo.One, PersistTo.One); if (!result3.Success) Console.WriteLine("This will also fail if I only have 1 node"); |

Each of these method calls will block until the desired Durability Requirements are met, and will allow your application to perform additional error handling.

Note that if the durability requirements fail, then Couchbase may still save the document and eventually distribute it across the cluster. All we know is that it didn’t succeed as far as the SDK knows. You can choose to act on this information to introduce more ACID properties into your application.

Final Notes

This blog post talked about the various primitives available to you in Couchbase to build ACID-like guarantees into your application. While these primitives do not satisfy full ACID definition, they are sufficient for what the vast majority of modern microservices-based applications need. For the small percentage of use cases that need additional transactional guarantees, Couchbase will continue to innovate further.

In the next post, we’ll look at techniques and sample code you might leverage to build a multi-document transaction in Couchbase.

If you have any questions, be sure to check out the Couchbase Forums. You can find the same code used in this blog post on Github.

Special thanks to all the co-authors of this blog post: Shivani Gupta, Ravid Mayuram, John Liang, Chin Hong, Matt Ingenthron, Michael Nitschinger (and I’m sure I’m missing a few others).

Matt, great post! I think it would also be helpful to discuss “consistency” within Couchbase in terms of document references and JOINs. i.e. that you can avoid typical problems of denormalization by referencing one document from within another. That way, when you make a write to either document, it is still ACID.

Thanks, Perry. I did discuss exactly that, except under ‘atomicity’ as I think it’s more applicable.

Thanks Matt, I do see that initial discussion there but I think it’s worth highlighting how multiple documents can still be updated “consistently” by showing the linkage between two documents and using a N1QL JOIN when reading them back. i.e. document1 contains most of my user profile and a pointer/reference to document2 which contains my list of orders. When I update document2, it is still consistent with the whole user profile when I read it back (via JOIN) even though I didn’t have to atomically update both document1 and document2. It’s this combination of normalisation and denormalisation that makes Couchbase so powerful and easy to achieve atomicity and consistency. Document1 is denormalised to contain multiple tables, but document1+document2 is normalised to prevent data bloat and improve concurrency…yet the combination is still atomic and consistent when updating either document (or any in a chain). Does that make more sense?