Important note: Multi-Document ACID Transactions are now available in Couchbase. See: ACID Transactions for NoSQL Applications for more information!

Multi-document transactions were not covered in the previous post in this series: ACID Properties and Couchbase. That blog post covered the building blocks of ACID that Couchbase supports for the single document. In this blog post, we’re going to use that foundation to build something like an atomic, distributed multi-document transaction.

Disclaimer: the code in this blog post is not recommended for production. It’s a stripped-down example that might be useful to you as-is, but will need hardening and polish before it’s ready for production. The intent is to give you an idea of what it would take for those (hopefully rare) situations where you need multi-document transactions with Couchbase.

A Brief Recap

In part 1, we saw that the ACID properties actually are available in Couchbase at the single document level. For use cases where documents can store data together in a denormalized fashion, this is adequate. In some cases, denormalization into a single document alone isn’t enough to meet requirements. For those small number of use cases, you may want to consider the example in this blog post.

A note of warning going in: this blog post is a starting point for you. Your use case, technical needs, Couchbase Server’s capabilities, and the edge cases you care about will all vary. There is no one-size-fits all approach as of today.

Multi-document transactions example

We’re going to focus on a simple operation to keep the code simple. For more advanced cases, you can build on this code and possibly genericize it and tailor it as you see fit.

Let’s say we are working on a game. This game involves creating and running farms (sounds crazy, I know). Suppose in this game, you have a barn which contains some number of chickens. Your friend also has a barn, containing some number of chickens. At some point, you might want to transfer some chickens from your barn to a friend’s barn.

In this case, data normalization probably will not help. Because:

- A single document containing all barns is just not going to work for a game of any significant size.

- It doesn’t make sense for your barn document to contain your friend’s barn document (or vice versa).

- The rest of the game logic works fine with single-document atomicity: it’s only the chicken transfer that’s tricky.

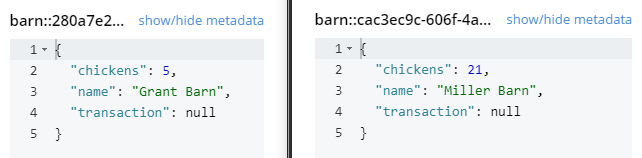

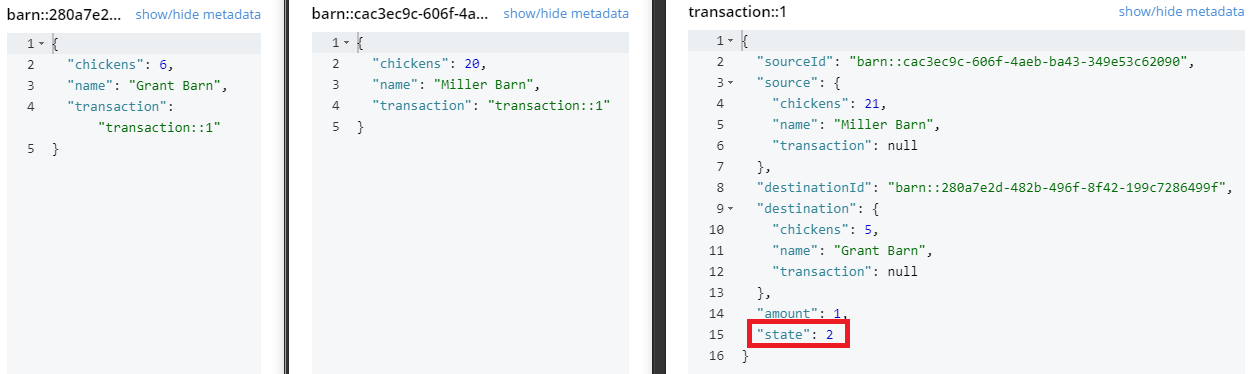

To begin with, all we have are two “barn” documents (Grant Barn and Miller Barn):

This method we’ll use to transfer chickens is called a “two-phase commit”. There are six total steps. The full source code is available on GitHub.

It occurred to me after taking all the screenshots and writing the code samples that chickens live in coops, not barns? But just go with me on this.

0) Transaction document

The first step is to create a transaction document. This is a document that will keep track of the multi-document transaction and the state of the transaction. I’ve created a C# Enum with the possible states used in the transaction. This will be a number when stored in Couchbase, but you could use strings or some other representation if you’d like.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 |

public enum TransactionStates { Initial = 0, Pending = 1, Committed = 2, Done = 3, Cancelling = 4, Cancelled = 5 } |

It will start out in a state “Initial”. Going into this transaction, we have a “source” barn, a “destination” barn, and some number of chickens to transfer.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 |

var transaction = _bucket.Upsert(new Document<TransactionRecord> { Id = transactionDocumentKey, Content = new TransactionRecord { SourceId = source.Id, Source = source.Value, DestinationId = destination.Id, Destination = destination.Value, Amount = amountToTransfer, State = TransactionStates.Initial } }); |

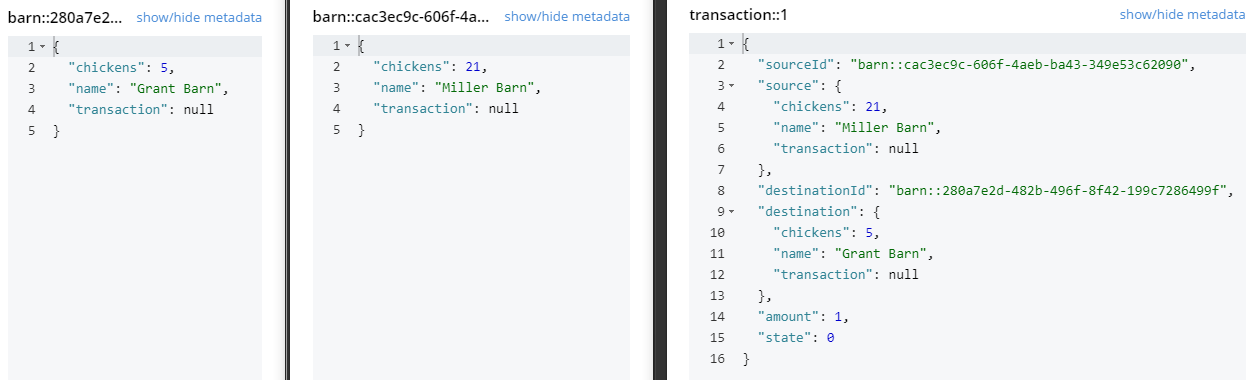

Let’s peek in on the data again. Now there are three documents. The transaction is new; the barn documents the same as they started.

1) Switch to pending

Next, let’s put the transaction document into a “pending” state. We’ll see later why the “state” of a transaction is important.

|

1 |

var transCas = UpdateWithCas<TransactionRecord>(transaction.Id, x => x.State = TransactionStates.Pending, transaction.Document.Cas); |

I’ve cheated a little bit here, because I’m using an UpdateWithCas function. I’m going to be doing this a lot, because updating a document using a Cas operation can be a bit verbose in .NET. So I created a little helper function:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 |

private ulong UpdateWithCas<T>(string documentId, Action<T> act, ulong? cas = null) { var document = _bucket.Get<T>(documentId); var content = document.Value; act(content); var result = _bucket.Replace(new Document<T> { Cas = cas ?? document.Cas, Id = document.Id, Content = content }); // NOTE: could put retr(ies) here // or throw exception when cas values don't match return result.Document.Cas; } |

That’s an important helper method. It uses optimistic locking to update a document, but doesn’t do any retries or error handling.

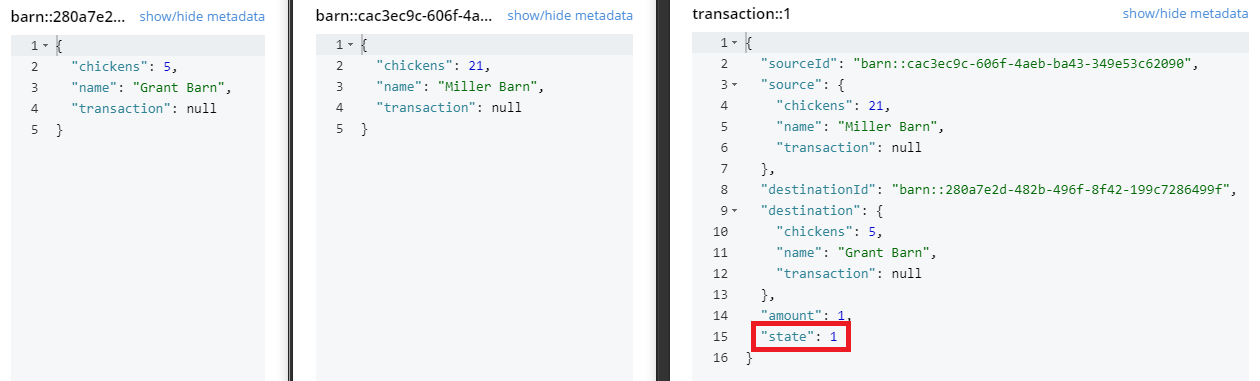

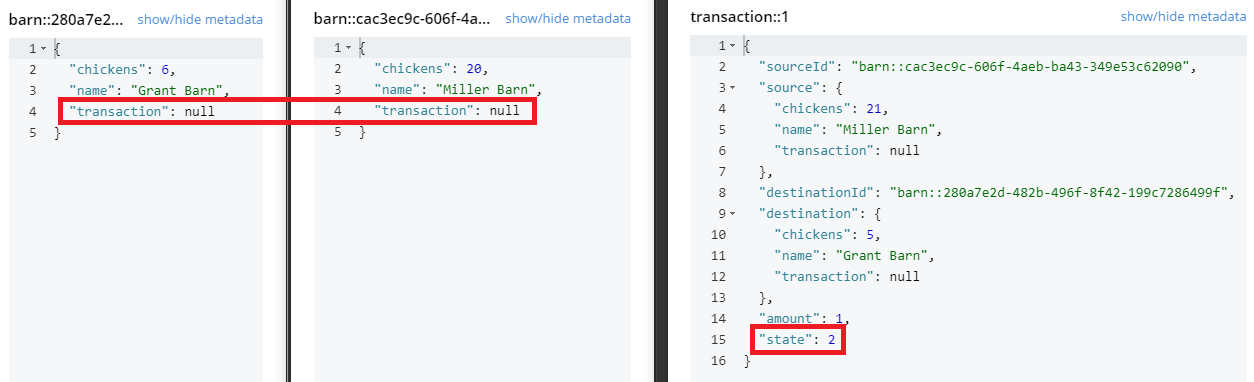

Let’s get back to the data., We still have three documents, but the transaction document “state” has been updated.

2) Change the documents

Next, we’ll actually perform the necessary mutations to the barn documents. Subtracting a chicken from the source barn, and adding a chicken to the destination barn. At the same time, we’re going to “tag” these barn documents with the transaction document ID. Again, you’ll see why this is important later. I’ll also store the Cas values of these mutations, because they’ll be necessary later when making further changes to these documents.

|

1 2 3 |

var sourceCas = UpdateWithCas<Barn>(source.Id, x => { x.Chickens -= amountToTransfer; x.Transaction = transaction.Id; }); var destCas = UpdateWithCas<Barn>(destination.Id, x => { x.Chickens += amountToTransfer; x.Transaction = transaction.Id; }); |

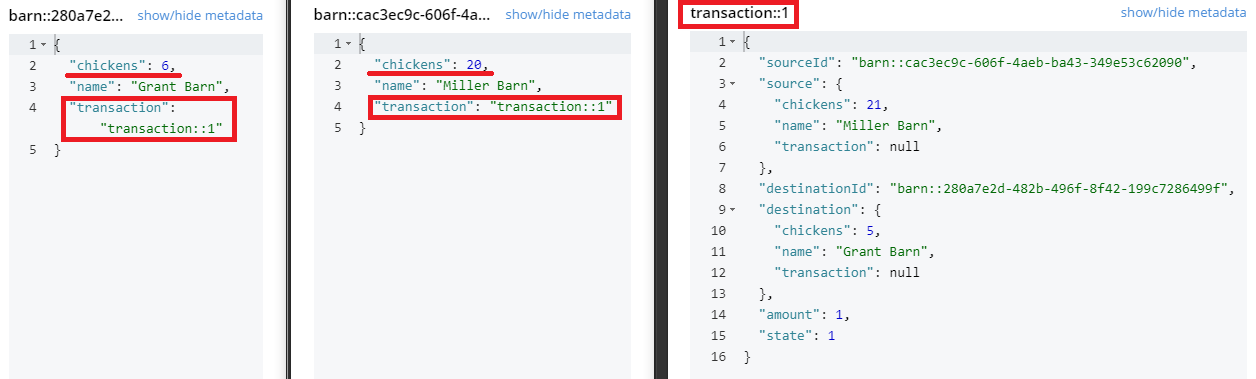

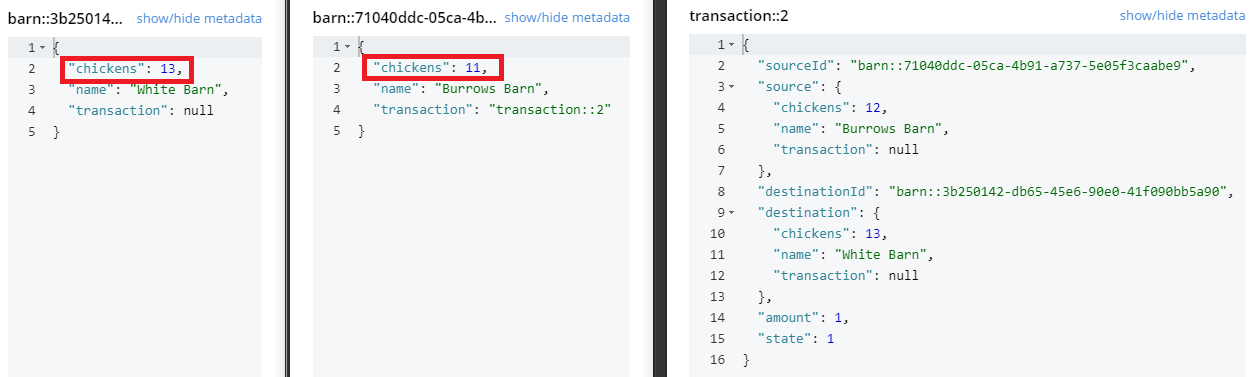

At this point, the code has moved a chicken between barns. Also notice the transaction “tag” on the barns.

3) Switch to committed

So far, so good. The mutations are complete; it’s time to mark the transaction as “committed”.

|

1 |

transCas = UpdateWithCas<TransactionRecord>(transaction.Id, x => x.State = TransactionStates.Committed, transCas); |

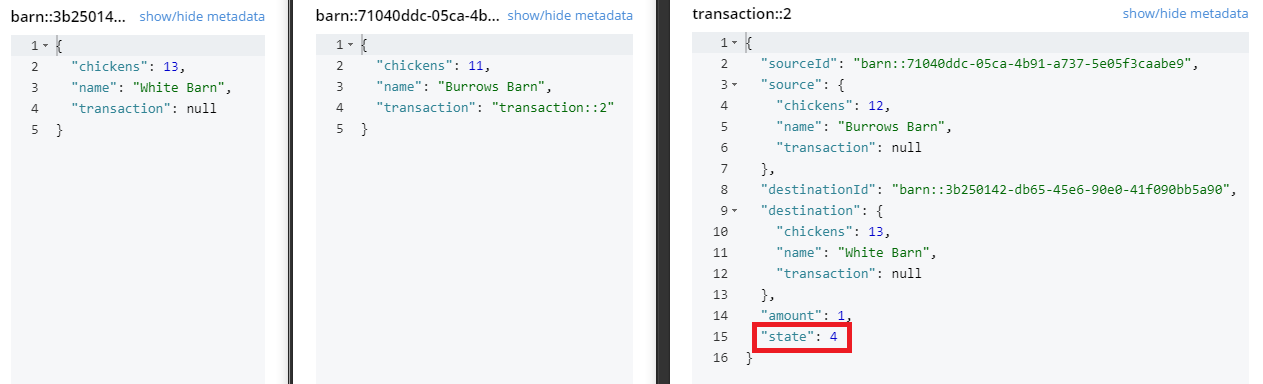

The only thing that changed is the “state” of the transaction.

4) Remove transaction tags

Now that the multi-document transaction is in a “committed” state, the barns no longer need to know that they’re part of a transaction. Remove those “tags” from the barns.

|

1 2 |

UpdateWithCas<Barn>(source.Id, x => { x.Transaction = null; }, sourceCas); UpdateWithCas<Barn>(destination.Id, x => { x.Transaction = null; }, destCas); |

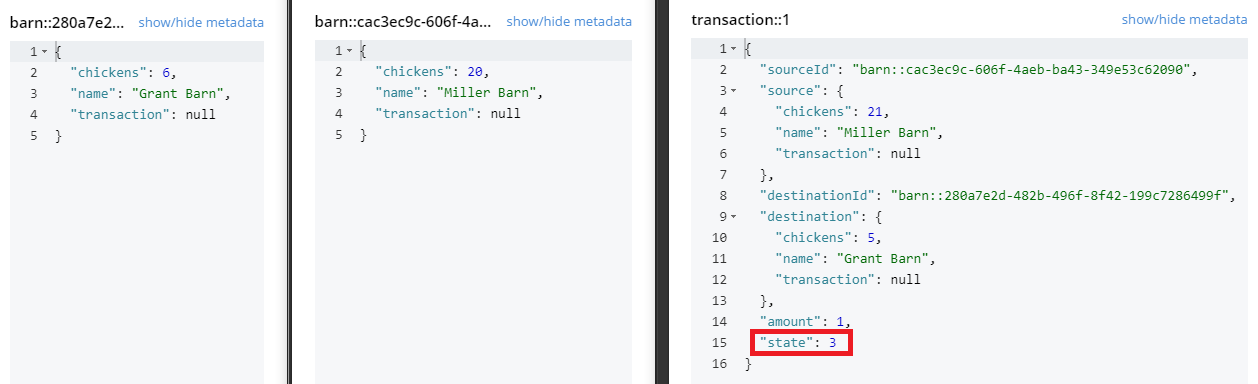

Now the barns are free from the transaction.

5) Transaction is done

The last step is to change the transaction state to “done”.

|

1 |

UpdateWithCas<TransactionRecord>(transaction.Id, x => x.State = TransactionStates.Done, transCas); |

If we’ve gotten this far, then the multi-document transaction is complete. The barns have the correct number of chickens after the transfer.

Rollback: what if something goes wrong?

It’s entirely possible that something goes wrong during multi-document transactions. That’s the point of a transaction, really. All the operations happen, or they don’t.

I’ve put the code for steps 1 through 5 above inside of a single try/catch block. An exception could happen anywhere along the way, but let’s focus on two critical points.

Exception during “pending” – How should we handle if an error occurs right in the middle of step 2. That is, AFTER a chicken is subtracted from the source barn but BEFORE a chicken is added to the destination barn. If we didn’t handle this situation, a chicken would disappear right into the aether and our game players would cry fowl!

Exception after transaction “committed” – The transaction has a state of “committed”, but an error occurs before the transaction tags are no longer on the barns. If we didn’t handle this, then it might appear from other processes that the barns are still inside of a transaction. The first chicken transfer would be successful, but no further chickens could be transferred.

The code can handle these problems inside of the catch block. This is where the “state” of the transaction comes into play (as well as the transaction “tags”).

Exception during “pending”

This is the situation that would lose chickens and make our gamers angry. The goal is to replace any lost chickens and get the barns back to the state they were before the transaction.

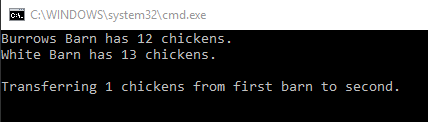

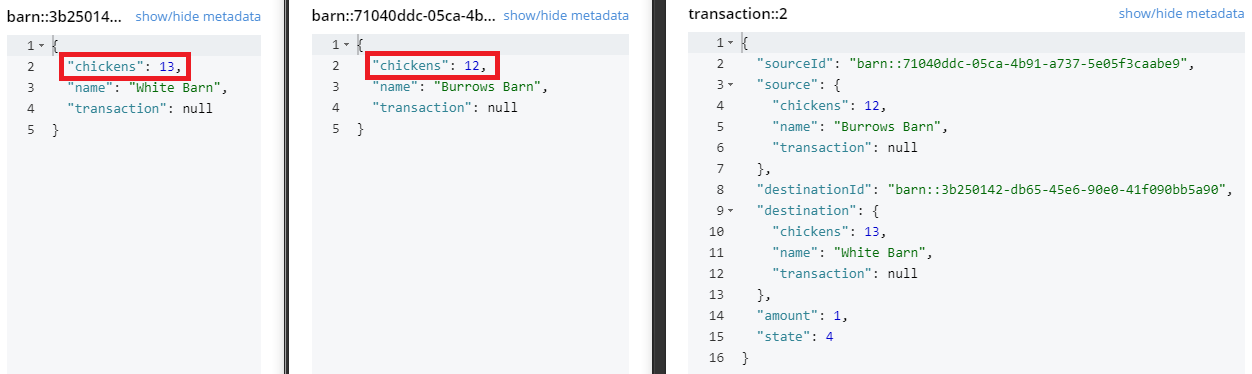

Let’s assume it happens right in the middle. For this example, we’ve got a new transaction: transfer 1 chicken from Burrows barn (12 chickens) to White barn (13 chickens).

An error happened right in the middle. The source barn has one less chicken, but the destination barn didn’t get it.

Here are the 3 steps to recovery:

1) Cancel transaction

Change the state of the transaction to “cancelling”. Later we’ll change it to “cancelled”.

|

1 |

UpdateWithCas<TransactionRecord>(transaction.Id, x => x.State = TransactionStates.Cancelling, transactionRecord.Cas); |

The only thing that’s changed so far is the transaction document:

2) Revert changes

Next, we need to revert the state of the barns back to what they were before. Note that this is ONLY necessary if the barn has a transaction tag on it. If it doesn’t have a tag, then we know it’s already in its pre-transaction state. If there is a tag, remove it.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 |

UpdateWithCas<Barn>(source.Id, x => { if (x.Transaction != null) { x.Chickens += transactionRecord.Value.Amount; x.Transaction = null; } }); UpdateWithCas<Barn>(destination.Id, x => { if (x.Transaction != null) { x.Chickens -= transactionRecord.Value.Amount; x.Transaction = null; } }); |

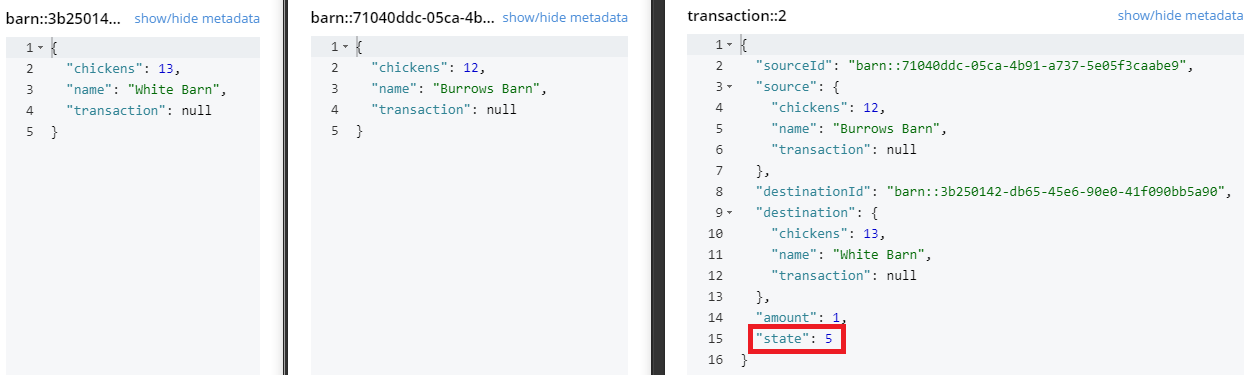

Now the barns are back to what they were before.

3) Cancelled transaction

The last thing to do is to set the transaction to “cancelled”.

|

1 |

UpdateWithCas<TransactionRecord>(transaction.Id, x => x.State = TransactionStates.Cancelled); |

And now, the transaction is “cancelled”.

This preserves the total number of chickens in the game. At this point, you still need to handle the error that caused the need for a rollback. You can retry, notify the players, log an error, or all of the above.

Exception during “committed”

Next, let’s look at another case: the changes to the barns are complete, but they have not yet had their transaction tags removed. Assuming the game logic cares about these tags, future multi-document transactions might not be possible.

The exact same rollback logic handles this situation as well.

Problems and edge cases

This simplified example may be just the trick for your application, but there are a lot of edge cases to think about.

What if the process dies part way through? This means that the code doesn’t even reach the catch block. You may need to check for any uncompleted multi-document transactions upon application startup and perform recovery there. Or possibly have a different watchdog process that looks for incomplete multi-document transactions.

What if there’s a read during the transaction? Suppose I “get” the barns right between their updates. This will be a “dirty” read, which can be problematic.

What state is everything left it? Whose responsibility is it to complete / rollback pending multi-document transactions?

What happens if the same document is part of two multi-document transactions concurrently? You will need to build in logic to prevent this from happening.

The sample contains all the state for rolling back. But if you want more transaction types (maybe you want to transfer cows)? You’d need a transaction type identifer, or you’d need to genericize the transaction code so that you can abstract “amount” used in the above examples and instead specify the updated version of the document.

Other edge cases. What happens if there’s a node in your cluster that fails in the middle of the transaction? What happens if you can’t get the locks you want? How long do you keep retrying? How do you identify a failed transaction (timeouts)? There are lots and lots of edge cases to deal with. You should thoroughly test all the conditions you expect to encounter in production. And in the end, you might want to consider some sort of mitigation strategy. If you detect a problem or you find a bug, you can give some free chickens to all parties involved after you fix the bug.

Other options

Our engineering team has been experimenting with RAMP client-side transactions. RAMP (Read Atomic Multi-Partition) is a way to guarantee atomic visibility in distributed databases. For more information, check out RAMP Made Easy by Jon Haddad or Scalable Atomic Visibility with RAMP Transactions by Peter Bailis.

The most mature example put together for Couchbase is from Graham Pople using the Java SDK. This is also not a production-ready library. But, Graham is doing some interesting stuff with client-side multi-document transactions. Stay tuned!

Another option is the open-source NDescribe library by Iain Cartledge (who is a Couchbase community champion).

Finally, check out the Saga Pattern, which is especially helpful for multi-document transactions among microservices.

Conclusion

This blog post talked about how to use the ACID primitives available to Couchbase to create a kind of atomic multi-document transaction for a distributed database. This is still not a completely solid replacement for ACID, but it is sufficient for what the vast majority of modern microservices-based applications need. For the small percentage of use cases that need additional transactional guarantees, Couchbase will continue to innovate further.

Thanks to Mike Goldsmith, Graham Pople, and Shivani Gupta who helped to review this blog post.

If you are eager to take advantage of the benefits of a distributed database like Couchbase, but still have concerns about multi-document transactions, please reach out to us! You can ask questions on the Couchbase Forums or you can contact me on Twitter @mgroves.

One of the strong points of Microservices is to send events during writes, to a topic and then have others such as views consume the event from the topic. In order to ensure that the event is sent to the topic, one simple and yet effective solution is to write the event in the DB (let say in a table called EventsToBeSent) along with the aggregate root for example, and have a worker which poll this table and pushes the events (in order) to the topic (Kafka for example).

You understand immediately that, it is nearly impossible to store the events in the AR so they need to be stored alone. To achieve this, with Couchbase, out of the box seems to be impossible, and using your approach seems to be extremely low.

Another possible solution is to store the event inside the AR document, and have the poller poll all the ARs with SELECT flat_array(ar.events) FROM bucket ar where type in (“AR1”, “AR2”, “AR3”) WHERE count(ar.events) > 0 sort by ar.timeStamp. But there are three main problems with this approach: 1) Queries are inconsistent in Couchbase (unless you use a trick for strong consistency), 2) The performance of this query itself in comparison to the old and battle proven RDBMS, 3) The performance of removing the events from the ARs. In an RDBMS you just do a simple UPDATE EventsToBeSent e SET e.IsSent = true WHERE e.Id in (,,,).